"Free steaming" is a Navy term meaning to act independently. Navy doctrine called for flagships to operate away from the fleets as part of the strategy to spread out targets in case of nuclear attack. The Oklahoma City almost always steamed alone, except when we were in the Gulf of Tonkin.

The ship spent quite a bit of time "showing the flag" in foreign ports as a part of its diplomatic mission. Liberty in these ports was really good, and we often received red carpet treatment. However, steaming between ports was a fairly monotonous routine. In addition to our regular watches we also had to carry out the routine ship's business.

A typical day at sea started about 0600 (6 AM). After a shower and shave we had breakfast and then mustered at 0800 for Officer's Quarters. The crew mustered at roll call - a head count to be sure everyone was still aboard. Then we did ship's work until noon. First seating in the Wardroom was for senior officers and junior officers going on watch at 1200. After that was the second seating for junior officers and officers coming off watch. The crew's mess also had two seatings. Afternoons saw more work, with two more seatings at evening meal. After that we had free time, with movies in the Ward Room and on the mess decks. Lights out was about 2100 (9 PM) to 2200 (10 PM).

Of course someone has to operate the ship 24 hours a day, so we had to work our watch schedule into the daily routine. While steaming between destinations we typically stood 1 in 4 watches - four hours at our watch stations followed by three watch periods when we worked, ate and slept. So we wouldn't have the same watch period each day there was a short two hour mid-watch from 0000 (midnight) to 0200, followed by another from 0200 to 0400. After this four hour watch periods were from 0400 to 0800, 0800 to 1200 (noon), 1200 to 1600, 1600 to 2000, and 2000 to 2400 (midnight). In potential combat situations we stood 1 in 3 watches, four hours on and eight off. This became very tiresome after two or three weeks without enough time for a decent sleep. When the ship was in combat we went to General Quarters, when everyone was at his combat station for as long as combat continued. Occasionally we executed drills of various sorts where everyone went to his duty station. All in all, it was difficult to keep a regular routine at sea and we worked and slept whenever we had the opportunity, day or night.

The navigation bridge was the control center when we were at sea. Here the Officer of the Deck (OOD) commanded the ship. The chair in the picture was the Captain's chair. By Navy tradition no one else was allowed to sit in it. The Captain spent much of the time at sea in that chair.

We had a radar repeater, gyro compass repeater, rudder angle indicators and other equipment for "conning" the ship. The red telephone sets were secure (scrambled) voice links to Pacific Fleet Headquarters, the Pentagon, etc. In port the handsets were removed. In addition to the Captain, OOD and JOOD (Junior Officer of the Deck) an enlisted sound powered phone talker was on the bridge to communicate with lookouts topside. To either side of the enclosed bridge were open wings that were used when maneuvering alongside other ships or pulling up to a pier.

Behind the bridge was the pilot house. The round brass wheel was the helm (steering wheel) that controlled the rudder, and the machine to the left of it was the lee helm that sent engine speed orders to the engine room. Overhead were four propeller RPM indicators. The helmsman and lee helmsman listened for orders from the OOD and carried them out. Also in the pilot house were the navigation watch stander and the bo'sun of the watch.

I took the pictures of the bridge and pilot house in port because when at sea the bridge is all business - no sightseers allowed. However, once while on bridge watch as JOOD I asked permission to take a picture, and here is what we saw when we were driving the ship. Not much to see but water, and that is about all you wanted to see! Boredom is OK when you are just sailing from point A to point B.

The complementary view is from the stern, looking at the ship's wake trailing off to the horizon. I'm here to tell you that there is a lot of water in the ocean! We typically steamed at 15 to 20 knots (nautical miles, or 17 to 23 miles per hour), though we could go about 32 knots if we were in a hurry. At 20 knots it took about four days to steam from Yokosuka, Japan to Yankee Station in the Gulf of Tonkin near DaNang, Vietnam.

While at sea the crew carried on routine business, like the Second Division men who were finishing the caulking of new deck boards and painting the bulkhead of a new compartment that was added during the last in-port period. The fellow on the right is preparing "McNamara's Lace" from a sheet of canvas. It was used for decoration on the Quarterdeck in port. Some people thought it was pretty, others thought it made us look like a circus ship.

A typical day would have people working on the engine in the motor whale boat, or the boat winches. Sometimes the Helo Detachment would be working on the Admiral's helicopter. Here we see the life nets and antennas on the fantail lowered for flight operations.

GM Division occasionally performed planned maintenance on the missile launcher. The Navy made statistical studies of the failure rates of all equipment on ships, and developed a planned maintenance schedule that allowed replacement of critical parts to be scheduled before they were expected to fail. The right hand picture shows work on the Talos emergency igniter. If a booster failed to ignite during a launch, the emergency igniter would ram a flammable charge up the tail pipe of the booster and light it.

One of the "evolutions" unique to the Okie Boat and other ships with wooden decks was "holystoning." We had teak decks extending from just aft of the anchor windlasses to a point forward of the missile launcher. To keep these looking pretty (we were a flagship, after all) the deck Divisions had to clean them regularly. The preferred method was holystoning.

This is a tradition that dates back to sailing ship days. A stone with a hole in it is placed at the end of a broom handle. A mixture of water and lye, oxalic acid, or some other bleach is poured onto the deck. Then the men scrub the deck with the stones to make it nice and white. This also requires a lot of elbow grease to get just the right finish. It was just another of the joys of being on a flagship.

I have heard that the name derived from the practice of sending crews to steal headstones from cemeteries, in Portsmouth, England, I think. This was the only reliable source of quality stones in the olden days. Modern (?) Navy practice in the 20th century was to use fire bricks removed from the boilers when they were periodically relined. It was more politically correct, and it was a ready source of stone that was not available in sailing ship days.

In addition to ordinary work we would also exercise at emergency drills while free steaming, to keep the crew in a state of readiness. General Quarters drills let us know how fast we could get ready for combat. Fire drills tested the condition of our fire fighting equipment, as well as the men themselves. Emergency in the missile house drills practiced the procedures for getting damage control crews into the restricted nuclear weapons spaces. Every now and then we would go to a gunnery range in the Philippines to practice direct firing with the five and six inch guns. When passing Okinawa we might launch a missile against a target drone. Here the motor whaleboat is being launched during a man overboard drill. If "practice makes perfect" we should have been pretty damned good!

Life at sea is not all work and no play. When not on duty we had some time to relax. Some guys liked to get suntans. Officers used "teak beach" on the fo'c'sl and enlisted men took in the rays on the fantail. After dinner the JOs (junior officers) often gathered on the fo'c'sl to shoot the breeze.

Card games were popular entertainment, although gambling was prohibited. It happened anyway - like the poker games in the missile house that I wasn't supposed to know about. Most evenings movies were shown in the wardroom and mess decks. We sometimes saw new movies before they were released Stateside, another bennie of having the Admiral aboard.

Our favorite duty was showing the flag. Sometimes our visits to ports of call were for recreation, and others were diplomatic visits. Whatever the reason, the ship would be all decked out in its finest trim. Usually we docked at a pier, and since we were the flagship, we often were given a special berth. In Hong Kong we tied up at the Officer's Club at HMS Tamar, the British Naval Base.

Occasionally we had to drop the hook. In this sequence of pictures you see the anchor detail waiting orders to let go the port anchor. The sailor on the left is holding a lanyard attached to the pin that locks the pelican hook closed. When the order came he pulled the pin and the fellow to his right swung a hammer to open the pelican hook that held the chain. Then ship's bo'sun CWO Hal Black watched the chain run until enough had played out. More chain was run out until yellow links came up on deck. Then the brakes were set and the crew attached the pelican hook "stopper" to hold the chain. Finally a second stopper was attached, just to be sure. When the hook was down the sailor on the bow hoisted the Union Jack on the jackstaff.

The yellow chain links were a warning that most of the chain had run out. Following these were red links. The round handles in the foreground controlled brakes on the wildcats that fed the chain out of the chain locker below deck. If the brakes failed and the chain could not be stopped, when the red links appeared everyone cleared the area as fast as possible. If the chain ripped free in the chain locker and the end came on deck, the flailing loose end could easily slice through the deck, gear locker, or any unfortunate sailor who was in the way.

When the ship was riding at anchor we took liberty boats ashore.

In some ports we held an open ship and allowed visitors to come aboard. For these occasions we ran out the TSAM trainer missiles and placed sign boards around the ship to explain the exhibits. Many thousands of people might visit the ship in an afternoon. On other occasions the locals came aboard and performed for the ship's company. This dance troop from Taiwan set up a stage on the fantail and put on quite a show.

Sometimes while at sea the Captain would throw a party for the crew. The mess decks would put together all the fixin's for a barbeque and we had a cookout on the fantail. The Seventh Fleet band set up by the missile launcher and everyone not on watch gathered 'round for food and entertainment. That's Captain Howell in the chair listening to the band play. Forward a boxing ring was set up for what, in Navy terms, is called a "smoker." A good time was had by all!

Every now and then we got some "entertainment" that we didn't plan. It might be good, like the beautiful sunsets and sunrises. We saw the "green flash" several times, and I even got a picture of it on one especially calm day.

Often the weather was not so nice. We encountered thunder storms with impressive lightning displays and rough seas caused by tropical storms. Consider the photo below of a huge wave. The picture doesn't convey the size of it unless you consider that it was taken from the deck of the ship, about 23 feet above the water. Now look where the wave rises above the line of the horizon - this point is about 20 feet above the base of the wave, so the crest is 35 to 40 feet high - as high as a four story building! Once when I was on the bridge I was looking up at green water crashing down from above. The navigation bridge deck was 65 feet above the waterline. The bow had plunged into a wave so the front of the ship was submerged, but still that wave had to be at least 60 feet high!

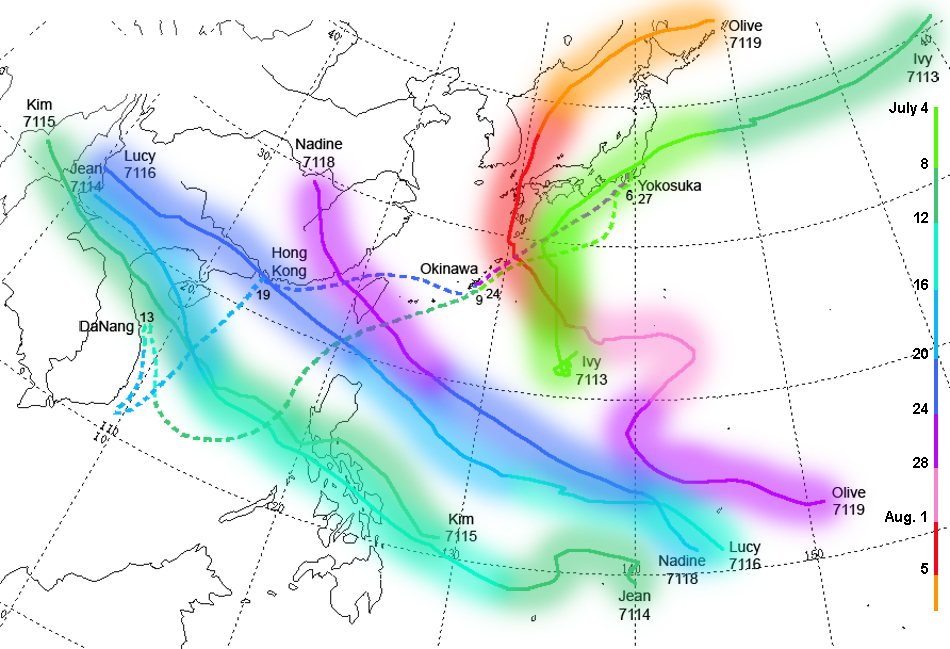

My most unforgettable cruise began on July 6, 1971. We were supposed to get underway on the 5th to go to Vietnam, but typhoon Ivy appeared south of Japan so we stayed in port a day to see where it was headed. It looked like it would cross southern Japan and move on to Korea, so we left on the 6th. Within a few hours the storm turned northeast, headed directly for us. We made a wide diversion to the south around the storm and passed through rough seas in its outer edge.

The trip was uneventful until we passed Taiwan and entered the South China Sea. Tropical storm Kim came across the Philippines and we had to change course to pass behind it, again crossing through heavy seas in the tail of the storm. Turning north we reached our Naval Gunfire Support station near DaNang. Two days later typhoon Jean came at us from the Philippines. Turning back southwest we raced into the leading edge of the storm before we turned south to let it pass. We were all pretty tired by this time. We had been at sea for a week and a half and half of that time had been in storms.

We were headed back to our station near DaNang when yet another storm started across the Philippines. It appeared to be heading for Vietnam so we turned north to take a rest in Hong Kong. Less than 24 hours after we arrived typhoon Lucy changed course directly for Hong Kong, and we got underway again, steaming east into heavy seas. We turned northeast along the China coast and dodged the storm. It bulls-eyed Hong Kong, causing tremendous damage.

Next typhoon Nadine came at us, crossing over Taiwan shortly after we passed. The storm weary ship pulled into White Beach in Okinawa for a rest and refueling. A few hours later typhoon Olive appeared bearing down on Okinawa, so once again we rushed into the leading edge of the storm and turned northeast to return to Japan. Even as we were making our way past Kyushu Olive turned north and crossed southern Japan. We arrived back at Yokosuka on July 27.

During the three week period we plowed our way through five typhoons and a tropical storm, and managed to dodge two other typhoons that were in WestPac. The chart tells the tale. Time is indicated by colors, as shown on the scale to the right. The Okie Boat's track is the colored dotted line, with dates shown along the track. The wide colored streaks are about 200 miles across, representing the cores of the storms. Heavy seas and strong winds extended for hundreds of miles in all directions.

These pictures were made just as we were leaving White Beach. After clearing the harbor we had to turn across the swells, with the danger of broaching in the heavy seas. The OOD on watch on the bridge later told me that the ship took one roll of 35 degrees, almost as far as she could go before turning turtle!

After taking the pictures topside I started down to the Wardroom for Sunday brunch. Just as I reached the door we took the heaviest roll, and throughout the ship you could hear crashes as equipment came loose and smashed to the deck. In one office a file cabinet ripped its anchors from the bulkhead and slammed around, pounding a typewriter into a nearly unrecognizable ball of crushed metal.

When I stepped into the wardroom I was greeted by an unfortunately comical sight. Sugar, cream, donuts, coffee, juice, smashed plates, glasses and cups, silverware and the remains of numerous breakfasts covered the deck. On this people, chairs and tables were sliding with the roll from one side of the space to the other. Only the head table was bolted down. At this the XO and two other officers were calmly finishing brunch, hanging on to the table and grabbing at passing plates and cups as they went by.

It was my unfortunate fate to suffer from motion sickness - seasickness. Part of it was psychological. After a few cruises I started feeling nauseous as soon as the last line was cast off from shore. I would get used to it in an hour or two and was OK if the seas were calm. Even with moderate pitching and rolling I just felt nauseous and rarely tossed my cookies. The fellows in CIC (Combat Information Center) said I attained an especially colorful shade of green. You might think three weeks in typhoons would have left me worshiping at the porcelain throne (actually, they were just steel), but in the worst weather we didn't have time to be sick. We were too busy just hanging on to something. Instead of nausea a deep fatigue set in, and a determination to get on with the routine no matter what. After weeks without letup everyone was exhausted.

Three weeks of pounding by heavy seas caused minor damage throughout the ship. The "bloomers" around the gun barrels on the 6-in/47 turret had to be replaced. At the end of the cruise as we steamed past O Shima on our way to Tokyo Wan, the view of Fuji san across Sagami Nada was a most welcome sight! We were happy to be home again in Yokosuka, and on solid ground.